Devil’s advocate: is there any real advantage of mini-invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy?

Introduction

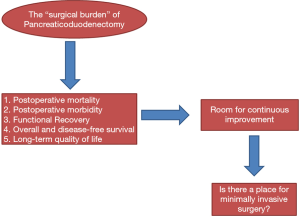

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is still considered to be one of the most technically complex procedures in digestive surgery. Coeliac and mesenteric vessels surround the anatomical location of the pancreas, so dissection of the pancreas is a specialized task. Since PD can potentially lead to digestive and pancreatic fistulas with consequent tissue and vessels erosions, patients need to be cared for in specialized high-volume units tended by well-trained physicians. The occurrence of such complications, which are prevalent and characterized by high mortality, requires prompt intervention by multidisciplinary teams (surgeons, interventional radiologist, and gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopist) (1,2). Physical recuperation from these complications, which sometimes require reoperation, can be particularly long and delay adjuvant chemotherapy, which consequently impacts cancer-related survival (3,4). Additionally, since digestive anatomy is largely modified by PDs, malabsorption and malnutrition can be common in the short and long term, which impacts quality of life and survival (5,6). All the above-mentioned issues indicate the current need to lessen the “surgical burden” of PDs (Figure 1). Could minimally invasive surgery (MIS) fulfill this need?

This question is far from answered. Many pancreatic surgeons are still reluctant to approach PD by minimally invasive-laparoscopy or robotic-assisted-surgery. In this article, we will play the role of devil’s advocate in order to objectively and subjectively identify advantages and grey areas of MIS for PD. This article will try to address four basic questions: (I) why is there reluctance to approach PD by MIS? (II) How safe is PD? (III) How oncologically effective is PD? (IV) What are the demonstrated advantages of PD?

Why is there reluctance to approach PD by MIS?

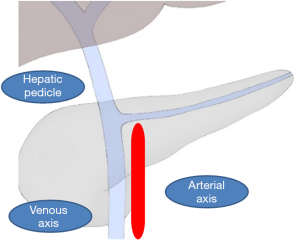

PD presents a unique peculiarity. Pancreatic resection requires specialized proficiency in dissection around the venous and arterial vessels of the coeliac and mesenteric system, which can be the source of perioperative life-threatening bleeding. The reconstructive phase of PD requires extensive experience to perform since leaks from pancreatic, bile, and gastric anastomoses are the main determinants of postoperative mortality and morbidity. The learning curve of PD is steep; a surgeon typically needs to perform 60 cases before they will have developed the surgical skills to perform a PD with reduced blood loss, operative time, and length of hospital stay (7). From a technical point of view, the dissection phase presents its own difficulties when using laparoscopy. PD is, in fact, a multi-quadrant procedure in which at least three different quadrants can be identified (Figure 2). The hepatic pedicle stands longitudinally to the surgeon’s view and the venous and the arterial axes are both located above and below the transverse mesocolon. While the venous axis is superficially located, the arterial axis is more deeply located, and its dissection can be particularly challenging in obese patients. The dissection of these three quadrants requires meticulous placement of the operative trocars and scope in order to achieve precise dissection.

Using the straight and rigid laparoscopic instruments, which have a limited degree of freedom, add some degree of difficulty to this dissection. Even though using vessels-sealer devices greatly helps, it can be particularly challenging to control bleeding along the venous axis. Many surgeons are probably reluctant to embrace this approach due to fear of not being able to properly control bleeding in a timely fashion.

During the reconstructive phase, suturing of the fragile pancreas and/or the thin bile duct can add technical challenges in laparoscopy even though the magnified view from laparoscopy could somewhat facilitate this task (8). Pancreatic and biliary anastomoses are still hand-sewn while stapler-assisted techniques are largely utilized for MIS rectal, esophageal and gastric surgeries.

In addition, the reconstructive phase often occurs with unpredictable timing after the completion of the long phase of dissection. Consequently, surgeons often become fatigued during the procedure, but this can be attenuated by using a two-surgeon technique (9). In order to avoid suturing of the pancreas, purse-string anastomoses may be the solution in cases such as open pancreatic surgery (10). Biliary anastomoses still can be challenging to perform, but, again, the magnified view of the laparoscope can be of great help.

Another point of debate concerns the technical skills required for this reconstructive operation. Pancreatic surgery requires specific training after residency in dedicated HPB fellowships programs. Besides being trained in laparoscopic exposure during residency programs, few pancreatic surgeons have been trained to perform the advanced digestive laparoscopic procedures that upper-GI surgeons and bariatric surgeons have typically been trained to do. The latter specialties usually have had greater exposure to laparoscopic suturing, which can help in this type of procedure (11).

Lastly, another point of debate is represented by the learning curve of this procedure, in which surgeons need experience from roughly forty to eighty cases to reach proficiency (12,13). The ongoing, multicenter prospective randomized TJDBPS01 trial has set a minimal surgeon requirement that surgeons should have personal experience with 104 MIS PDs to operate on patients (14). This probably indicates a longer learning curve than open surgery and is the highest technical requirement compared to the previous three randomized studies (15-17). Since few centers are performing MIS PD, the standard for training surgeons for this procedure represent a real problem (18)

Is minimally invasive PD safe?

Three randomized controlled trials and several retrospective studies have largely demonstrated the safety of MIS (15-17,19-27). From an analysis of the literature, the range of postoperative mortality, morbidity, and pancreatic specific complications seems to be comparable to open surgery. Laparoscopy and robotics appear to not increase the rate of specific complications of pancreatic surgery or their severity. One could hypothesize, in fact, that since few adhesions are present after a MIS approach, every form of leak may be even more dangerous than in open surgery. This however could not be confirmed by published results. However, it should be noted that few authors matched subjects according to their pancreatic fistula risk score and all these comparisons present a noteworthy selection bias. The LEOPARD-2 trial was prematurely interrupted because of a difference in 90-day complication-related mortality [5 (10%) of 50 patients in the laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy group vs. 1 (2%) of 49 in the open pancreatoduodenectomy group; risk ratio (RR) 4.90 (95% CI: 0.59–40.44); P=0.20] potentially suggesting a difference in complications or its management that were not captured by the classification systems used (17). In addition, a registry study from the US reported an increased readmission rate for MIS PD but lacked details regarding the reasons for readmissions and pancreatic-specific complications (24).

Surgeon conversion from MIS to open surgery seems to be negatively related to experience but reasons for conversion have been seldomly subjectively reported. In two of the three randomized studies, this rate approached 20% underlining the technical complexity of this operation (16,17). Lastly, there is a volume-effect that was important for MIS PD. In fact, Sharpe et al. found that the 30-day mortality was higher for MIS PD [odds ratio (OR): 2.27; P=0.002] at low-volume centers (<10 MIS PDs/2 years) whereas it was the same (OR: 0.46; P=0.428) at high-volume centers (>10 MIS PDs/2 years) (25). The same finding was reported by a metanalysis by De Rooij et al. who found that mortality after MIS PD was increased in low-volume hospitals (7.5% vs. 3.4%; P=0.003) (21).

Is minimally invasive PD oncological effective?

Pancreatic resections are mostly performed for cancer with margin status, survival and long-term quality of life as the major quality metrics. Few studies have evaluated the oncological effectiveness of MIS for PD in adenocarcinoma cases. However, at least five comparative studies and one metanalysis found similar results in term of the number of harvested lymph nodes (LN) and rate of R0 resections (19,20,22,23,26,27). Additionally, it seems that patients undergoing MIS PD had higher rates of 3-year (OR 1.50, 95% CI: 1.12 to 2.02, P=0.007), 4-year (OR 1.73, 95% CI: 1.02 to 2.93, P=0.04), and 5-year survival (OR 2.11, 95% CI: 1.35 to 3.31, P=0.001) than open surgery counterparts (19). It should be noted, however, that there was not a randomized trial and that there was probably a selection bias toward less advanced cases that were included in the MIS groups. For example, some of these studies reported that the MIS groups exhibited inferior tumor sizes (22,26,27) and fewer positive LN (26). Resection margin status was also assessed using different protocols throughout these studies. Additionally, data on the rate of administered adjuvant chemotherapy and the type of recurrences, which should be considered important outcomes when dealing with new surgical approaches, were not available in some studies (22,23,26). The time it took MIS PD patients to receive adjuvant treatment was reported in two studies (20,27), but the rates were similar between open and laparoscopic surgery.

Does minimally invasive PDs have advantages over open PD?

Several retrospective studies and consequent metanalyses have clearly showed that MIS PD achieves statistically significantly decreased blood loss and reduced length of hospital stay at the expense of increased operative time and readmission rate compared with open PD (13,17,21). This reduction in blood loss may reflect less advanced cases that were operated by MIS. However, like liver surgery, this decrease in blood loss is certainly related to the magnified view of laparoscopy and the fact that continuous hemostasis is necessary in order to not lose an accurate view of the operative field. This reduction in blood loss could be associated with a significant advantage on survival since increased blood loss has been associated with impaired survival in surgical oncology (28). Reduction in hospital stay was not consistently reported across the published and readmission rate was reported to be higher (24). This could be probably attributed to the fact that readmission is due to pancreatic specific complications that do not differ in severity between MIS and open surgery. Details regarding the time it took patients to receive adjuvant chemotherapy, functional recovery, and quality of life were lacking in most of the studies.

Conclusions

There still is reluctance to embrace a minimally invasive approach for PD by pancreatic surgeons. This is largely due to the technical complexity of the operation, which requires advanced training and experience in laparoscopic and pancreatic surgery. Morbidity and mortality of MIS PD seems to be comparable to open surgery, but a recent randomized trial was prematurely interrupted due to higher mortality in the laparoscopic arm (17). Long-term survival of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma seems to be comparable between MIS PD and open surgery. MIS PD achieves statistically significantly decreased blood loss at the expense of increased operative time compared with open PD. Quality metrics and new scores should be developed in order to further evaluate and compare the outcomes from open and/or MS pancreatic resection.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Edoardo Rosso) for the series “Mini-invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy: are we moving from a “feasible” intervention to be considered the standard?” published in Laparoscopic Surgery. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ls-20-60). The series “Mini-invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy: are we moving from a “feasible” intervention to be considered the standard?” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The author has no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Strobel O, Neoptolemos J, Jager D, et al. Optimizing the outcomes of pancreatic cancer surgery. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2019;16:11-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gooiker GA, van Gijn W, Wouters MW, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the volume-outcome relationship in pancreatic surgery. Br J Surg 2011;98:485-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamphues C, Bova R, Schricke D, et al. Postoperative complications deteriorate long-term outcome in pancreatic cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:856-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mackay TM, Smits FJ, Roos D, et al. The risk of not receiving adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a nationwide analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2020;22:233-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Allen CJ, Yakoub D, Macedo FI, et al. Long-term Quality of Life and Gastrointestinal Functional Outcomes After Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 2018;268:657-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto D, Chikamoto A, Ohmuraya M, et al. Impact of Postoperative Weight Loss on Survival After Resection for Pancreatic Cancer. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2015;39:598-603. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tseng JF, Pisters PW, Lee JE, et al. The learning curve in pancreatic surgery. Surgery 2007;141:456-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chopinet S, Fuks D, Rinaudo M, et al. Postoperative Bleeding After Laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy: the Achilles' Heel? World J Surg 2018;42:1138-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Turrini O, Delpero JR. Two surgeons for one pancreas. ANZ J Surg 2008;78:1140-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Addeo P, Rosso E, Fuchshuber P, et al. Double purse-string telescoped pancreaticogastrostomy: an expedient, safe, and easy technique. J Am Coll Surg 2013;216:e27-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Birkmeyer JD, Finks JF, O'Reilly A, et al. Surgical skill and complication rates after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1434-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boone BA, Zenati M, Hogg ME, et al. Assessment of quality outcomes for robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy: identification of the learning curve. JAMA Surg 2015;150:416-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nickel F, Haney CM, Kowalewski KF, et al. Laparoscopic Versus Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann Surg 2020;271:54-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang H, Feng Y, Zhao J, et al. Total laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy (TJDBPS01): study protocol for a multicentre, randomised controlled clinical trial. BMJ Open 2020;10:e033490 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palanivelu C, Senthilnathan P, Sabnis SC, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for periampullary tumours. Br J Surg 2017;104:1443-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poves I, Burdio F, Morato O, et al. Comparison of Perioperative Outcomes Between Laparoscopic and Open Approach for Pancreatoduodenectomy: The PADULAP Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg 2018;268:731-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Hilst J, de Rooij T, Bosscha K, et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours (LEOPARD-2): a multicentre, patient-blinded, randomised controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;4:199-207. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hogg ME, Besselink MG, Clavien PA, et al. Training in Minimally Invasive Pancreatic Resections: a paradigm shift away from "See one, Do one, Teach one". HPB (Oxford) 2017;19:234-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen K, Zhou Y, Jin W, et al. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: oncologic outcomes and long-term survival. Surg Endosc 2020;34:1948-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Croome KP, Farnell MB, Que FG, et al. Total laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: oncologic advantages over open approaches? Ann Surg 2014;260:633-8; discussion 638-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Rooij T, Lu MZ, Steen MW, et al. Minimally Invasive Versus Open Pancreatoduodenectomy: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Comparative Cohort and Registry Studies. Ann Surg 2016;264:257-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dokmak S, Fteriche FS, Aussilhou B, et al. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy should not be routine for resection of periampullary tumors. J Am Coll Surg 2015;220:831-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuesters S, Chikhladze S, Makowiec F, et al. Oncological outcome of laparoscopically assisted pancreatoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma in a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg 2018;55:162-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nassour I, Wang SC, Christie A, et al. Minimally Invasive Versus Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Propensity-matched Study From a National Cohort of Patients. Ann Surg 2018;268:151-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sharpe SM, Talamonti MS, Wang CE, et al. Early National Experience with Laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy for Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Comparison of Laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy and Open Pancreaticoduodenectomy from the National Cancer Data Base. J Am Coll Surg 2015;221:175-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Song KB, Kim SC, Hwang DW, et al. Matched Case-Control Analysis Comparing Laparoscopic and Open Pylorus-preserving Pancreaticoduodenectomy in Patients With Periampullary Tumors. Ann Surg 2015;262:146-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stauffer JA, Coppola A, Villacreses D, et al. Laparoscopic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: long-term results at a single institution. Surg Endosc 2017;31:2233-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mavros MN, Xu L, Maqsood H, et al. Perioperative Blood Transfusion and the Prognosis of Pancreatic Cancer Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:4382-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Addeo P. Devil’s advocate: is there any real advantage of mini-invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy? Laparosc Surg 2021;5:21.