Feasibility and safety of outpatient minimally invasive adrenalectomy: a scoping review

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and the stress it induced on healthcare systems has prompted a re-evaluation of the feasibility of performing traditionally inpatient surgical procedures in an outpatient fashion (1-3). In the setting of a global pandemic, same-day surgery can minimize the utilization of limited resources and personnel as well as decrease the risk of disease transmission. Given that they are already associated with a short hospital stay, endocrine surgical procedures such as minimally invasive adrenalectomy appear to be prime candidates for day surgery.

Specifically for adrenalectomy, performing the procedure in an outpatient fashion is not a new concept. Small-scale studies in the early 2000s (4-7) have demonstrated the feasibility of outpatient adrenalectomy. Yet, two decades later, widespread adoption and formal endorsement of ambulatory adrenalectomy by professional societies is lacking. As of February 2022, laparoscopic adrenalectomy remains on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Inpatient Only Procedure List; that is, if the procedure is performed on an outpatient basis, it is at risk for being denied reimbursement along with other services performed on the same claim (8,9). Indeed, among patients undergoing an elective laparoscopic adrenalectomy between 2005–2016 (10) and 2011–2017 (11) included in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) dataset, fewer than 2% were discharged on the same day. Though insurers do not consider this procedure for an outpatient setting, outpatient performance of minimally invasive adrenalectomy can offer several benefits if carefully balanced with risks. These include reduced health-care resource costs and utilization, and decreased patient exposure to hospital-acquired conditions (12).

With this review we aimed to systematically evaluate the published literature on outpatient minimally invasive adrenalectomy (OMIA), focusing on its feasibility, safety, advantages and limitations. Our synthesis of findings could potentially facilitate the adoption or creation of consensus guidelines on this topic as well as identify specific areas where further investigation is needed. We present the following article in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR reporting checklist (available at https://ls.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ls-22-23/rc) (13).

Methods

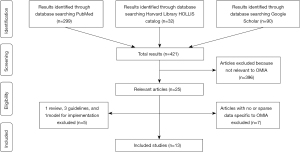

In this systematic literature review performed in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR guidelines (13), we included studies presenting data on OMIA. Our definition of outpatient adrenalectomy comprised laparoscopic transabdominal, posterior retroperitoneoscopic, and robotic cases in which patients were discharged the same calendar day as the surgery; studies focusing on short-stay adrenalectomy with less than 23 or 24 h stay, but inclusive of discharge on a subsequent calendar day, were not included [e.g., (7,14)]. A search of PubMed, Harvard Library HOLLIS catalog, and Google Scholar databases was performed. All sources were last searched on January 31, 2022. PubMed searches used the medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and single search terms as described: ((((“Ambulatory Surgical Procedures”[Mesh]) OR (ambulatory)) OR (same day)) OR (outpatient)) AND ((adrenalectomy) OR (“Adrenalectomy”[Mesh])). In Google Scholar and the Harvard Library HOLLIS catalog, the search terms “outpatient adrenalectomy” and “same-day adrenalectomy” were used. References of included articles were screened by title (TM, DA) for relevant papers. Studies on open (i.e., not minimally invasive) adrenalectomies, as well as studies published in a language other than English, were excluded. Given the limited number of relevant studies and small cohorts, conference abstracts were also included.

A data-charting form was jointly developed by three reviewers (TM, DA, RG). Data from included studies were charted manually into a spreadsheet. Data were charted independently by two reviewers (TM, DA) and consensus was achieved in case of discrepancies. Extracted data included study-specific characteristics (e.g., study type, patient selection criteria, location, accrual years), patient sociodemographic and anthropometric factors [e.g., age, gender, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status class], pathologic characteristics (e.g., tumor type and size), as well as perioperative factors (e.g., surgical approach, estimated intraoperative blood loss, operative time, length of hospital stay). Outcomes of interest included complication rate, readmission rate, rate of return to the operating room, patient satisfaction, cost and mortality. Given the heterogeneity in study design, methods and endpoints, as well as the small study samples, a meta-analysis was not performed. A review protocol is not available for this study and this review was not registered.

Results

Included studies

Our search terms yielded 421 results (Figure 1). From this search, twenty-five relevant articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Of these, seven studies which mentioned OMIA but had no OMIA-specific data (6,15-20), one article presenting a model for implementation (21), one editorial brief review on the practice (22), and three guideline statements (23-25) were excluded. Thirteen studies were ultimately included (Table 1). Most studies were retrospective single-center reviews of a single cohort and did not include direct comparisons with inpatient adrenalectomy cases. Our search yielded no randomized controlled trials or Cochrane reviews.

Table 1

| Study | Location | Years of the study | No. of pts undergoing laparoscopic adrenalectomy, inpatient or outpatient | No. of pts undergoing outpatient adrenalectomy (discharge on same calendar day) | Female pts (%) (when applicable: total/undergoing outpatient adrenalectomy) | ASA class III or above (when applicable: total/undergoing outpatient adrenalectomy) | Type of study | Age range (when applicable: total/undergoing outpatient adrenalectomy) | Indications for adrenalectomy (when applicable: total/undergoing outpatient adrenalectomy) | Pt cohort was drawn from this group | Pt selection or exclusion criteria | Tumor exclusion criteria | Estimated blood loss (mL) (if applicable: total/undergoing outpatient adrenalectomy) | Operative time (min) (if applicable, total/undergoing outpatient adrenalectomy) | Length of hospital stay (if applicable: total/undergoing outpatient adrenalectomy) | Mortality rate after laparoscopic adrenalectomy (if applicable: total/undergoing outpatient adrenalectomy) | Rate of return to the operating room (if applicable: total/undergoing outpatient adrenalectomy) | Complication rate (if applicable: total/undergoing outpatient adrenalectomy) | Readmission rate (if applicable: total/undergoing outpatient adrenalectomy) | Complications | Patient satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abaza 2021 (26) | OhioHealth Dublin Methodist Hospital, Dublin OH; Ohio Univ. Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Dublin, OH | 01/ 2019–01/2020 | 4 | 4 | – | – | Single surgeon (RA) prospective study | – | – | 100 first single port robotic surgeries with the da Vinci system after its adoption in 2019 |

Selected for pts who have immediate ambulation, immediate diet, and scheduled non–narcotic analgesia with optional oral but no IV narcotics | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0% | – | – |

| Cabalag 2014 (27) | Melbourne Epi Centre, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Victoria, Australia | 05/2011–09/2013 | 49 pts (50 adrenalectomies) | 8 (16%) | 66% | – | Single surgeon prospective study | 58.5 median (range 30–83)/– | 25 functional adrenal neoplasms, 20 non-functioning adrenal masses, and 5 solitary metastases | 50 consecutive posterior retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomies performed by same surgeon | – | Primary adrenal malignancy (not offered minimally invasive surgery) | – | 70.5 median [54–85]/– | 1 night median (1–1) | 0% | – | – | – | – | – |

| Edwin 2001 (5) | Ullevaal Hospital, Univ. of Oslo, Norway | 03/1999–07/2000 (date of paper submission) | 13 | 13 | 46% | – | Multi-center retrospective study | – | Pts referred to outpatient laparoscopic adrenalectomy protocol; all happened to have Conn syndrome | 13 selected pts entered into outpatient laparoscopic adrenalectomy protocol | Selected for pts who lived within 30 m from hospital, with adult company present at home | Excluded pheochromocytoma, large tumors >10 cm, and histologically verified adrenal carcinoma | – | 38 mean [35–112] |

3–6 h | – | – | 15% | 0% | Postoperative fever reaction with increased CRP | Excellent in all but one case due to pain on 1st post–op day |

| Gagné 2007 (28) | Freestanding ambulatory center part of Ottawa Hospital, the Academic Health Science Center of the Univ. of Ottawa | “Over 3 years” | 5 | 5 | – | – | Single-center retrospective study | – | Conn’s disease in 3 cases and incidentalomas in 2 cases | 5 outpatient adrenalectomies done over 3 years in this program | – | – | – | 140 median | – | 0% | – | – | – | – | – |

| Gartland 2021 (29) | Univ. Alabama at Birmingham Medical Center, Birmingham, AL; Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA | 1st AMC: 6/2016–12/2019; 2nd AMC: 10/2017–12/2019 | 203 | 99 (49%) | 58%/56% | 70%/64%^^^^ | Multi-center retrospective study | 56 median (IQR: 45–67)/56 (IQR: 47–66) |

Nodule/mass (38%/43%), primary hyperaldosteronism (21%/27%), concern for pheochromocytoma (21%, 14%), Cushing’s syndrome (15%, 14%), metastasis or concern for metastasis (4%/1%) | All pts at 2 academic medical centers undergoing minimally invasive adrenalectomy starting from the time outpatient adrenalectomy was initiated at each institution | No strict criteria but decided on day of surgery based on care itself, patient's recovery in postanesthesia care unit, pt overall comfort/readiness for discharge (which was often related to time of day, distance of home from hospital, and level of support at home) | Excluded removal of other organs, bilateral adrenalectomies, and cases in which a pt was admitted to the hospital before the day of the surgery | 25 median (IQR: 10–50)/20 (IQR: 10–30) |

93 median (IQR: 71–134)/91 (IQR: 73–132) | – | 2.5%/1% | – | 9.9%/4% (within 30 d) |

4.9%/2% (within 30 d) |

Hematoma, superficial site infection, lower extremity pain and paresthesia, and UTI | – |

| Gill 2000 (4) | Section of Laparoscopic and Minimally Invasive Surgery, Dept of Urology and Dept of Hypertension/Nephrology, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, Ohio | 09/1998–09/1999 | 9 | 9 | 33% | – | Single-center prospective study | 52.6 mean (range 37–66) | Aldosteronoma in 7 of 9 cases, enlarging nonfunctioning adenoma in 1 and myelolipoma in 1 | Select pts who underwent outpatient laparoscopic adrenalectomy protocol | Preoperative criteria: pt/family must be agreeable to outpatient surgery, good family support system, no pheochromocytoma, adrenal tumor ≤5 cm, no active cardiac disease, blood pressure well controlled on 3 or fewer antihypertensive medicines, age ≤70, BMI ≤40; Intraoperative criteria: procedure completed without any intraoperative complications, surgery completed by noon; Postoperative criteria: no postoperative complications, hemodynamically stable, walking without difficulty, abdomen soft, tolerating liquids orally, pain under control on oral analgesics | Excluded pheochromocytoma as well as adrenal tumors 5cm or greater | 53 (mean) | 135 mean | 416 m mean (range 300–570) |

0% | 11% | 11% | 11% | Local abscess requiring delayed drainage at 2 weeks |

High overall satisfaction; for outpatient, 0.3 average with 0= completely satisfied and 10= completely dissatisfied, 0.6 for conventional |

| Mohammad 2009 (30) | The Ottawa Hospital, Univ. of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada | 1994–2006 | 17 | 14 (note: 3 pts stayed for 23 h, analyses were reported for all 17 patients) | 71% | – | Single-surgeon retrospective study | 52.4 mean (range 29–71) | Aldosteronoma in 11 of 17 cases, 3 incidentalomas that turned out to be benign cortical adenomas, 2 Cushing syndrome, and 1 solitary metastasis | 17 outpatient adrenalectomies performed by single surgeon from 1994–2006 | Age less than or equal to 75 years, no significant cardiopulmonary morbidities (ASA I and II), only 3 or less antihypertensive medications, first case of the day, and home stay is 1 h or less from Ottawa | Excluded pheochromocytoma, Cushing syndrome, and tumor size over 6 cm | – | 130 mean | 5.5 h mean | 0% | 0% | 8% | 0% (within 30 d) | Atelectasis with oxygen saturations less than 90% | – |

| Moughnyeh 2020 (31) | University of Alabama at Birmingham Medical Center, Birmingham, AL | 01–10/2018 | 15 | 15 | 60% | Mean ASA score was III | Single-surgeon retrospective study | 58 (mean) ±4 | 7 functional adrenal masses (3 Cushing syndrome, 2 hyperaldosteronism, 2 pheochromocytoma) and 8 nonfunctional masses | Pts who underwent outpatient robot-assisted adrenalectomies with a single high-volume adrenal surgeon | – | – | – | 134 (mean) ±10 | 205 (mean) ±18 min | 0% | 0% | 7% | 7% (within 30 d) | Adrenal insufficiency | – |

| Pigg 2022 (32) | University of Alabama at Birmingham Medical Center, Birmingham, AL | 2017–2020 | 58 | 33 (57%) | – | – | Single-center survey | >18 | Indications included nodule/mass, primary hyperaldosteronism, Cushing’s syndrome, metastasis/concern for metastasis | Institutional database queried for adrenalectomies and divided into inpatient and outpatient groups; both groups sent surveys | – | – | – | – | 12.8 h/2.8 h. All values given for survey respondents | – | – | 12%/6%. No difference in self-reported pain or complication rate compared to inpatient group among survey respondents (within 30 d) | 5.2%/0% (within 30 d) | – | No statistically significant difference between satisfaction inpatient vs. outpatient. Patient satisfaction significantly associated with self-reported degree of preparation for surgery and discharge; pts undergoing outpatient adrenalectomy are more likely to have their discharge plan discussed preoperatively |

| Shariq 2021 (10) | ACS NSQIP data | 2005–2016 | 4,807 | 88 (1.8%) | 62% | 61%/46% | Multi-center retrospective study | 52 median (IQR: 42–62)/50.5 (IQR: 41.5–59.5) |

Nonfunctioning adenoma (61%/51%), Cushing’s syndrome (1.1%/0%), Primary aldosteronism (5.8%, 15%), other adrenal disorder (32%, 34%) | Adults who underwent elective laparoscopic adrenalectomy between 2005 and 2016 in the ACS NSQIP database | Excluded age <18 years; emergency operation; the following preoperative comorbidities: ventilator-dependency, sepsis, septic shock, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, pneumonia, acute renal failure, requirement for blood transfusion within 72 h before operation, dialysis, and open wounds; pts transferred to a separate acute care facility on discharge or whose discharge destination was “expired” | Excluded bilateral procedures, open conversion, concurrent major procedures like splenectomy or pancreatectomy, and malignancy excluded. Pheochromocytoma, emergency operation also excluded | – | 119 mean [89–160]/92 [71–110] | – | 0.2%/0% (30-day mortality) |

0% | 4.4%/3.4% (within 30 d) | 3.4%/5.7% (within 30 d) |

Bleeding, hormone related, infection, electrolyte/fluid imbalance | – |

| Sharma 2020 (11) | ACS NSQIP data | 2011–2017 | 5,611 | 93 (1.7%) | – | – | Multi-center retrospective study | – | – | Pts who underwent laparoscopic adrenalectomy between 2011 and 2017 in the ACS NSQIP database | – | – | – | – | 2.4 d/– | – | – | 6.3%/3.2% | 5.2%/4.3% (within 30 d) |

– | – |

| Skattum 2004 (33) | Ullevaal University Hospital, Oslo, Norway | 01/1994–05/2003 | 22 | 22 | – | – | Single-center prospective study | – | 100% with Conn’s disease | Pts who underwent laparoscopic adrenalectomy on an outpatient basis in the Day Surgical center | Excluded pts living >30 m drive from the hospital or unwillingness to stay in the hospital hotel over the first night, lack of availability of competent adult at home, personal inability to respond adequately to pain/discomfort (for example, mental retardation) | Excluded pheochromocytomas, suspected malignant tumors, tumors >10 cm | – | 45 (38–98) | – | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | – | Excellent or good in 90%, intermediate in 10% |

AMC, academic medical center; pt(s), patient(s).

Feasibility of OMIA

The feasibility of short-stay (<24 h) (7) and specifically OMIA was first described in several small studies in the early 2000s (4,5,7). Gill et al. presented a series of 9 patients no older than 70 years of age with non-pheochromocytoma adrenal tumors up to 5 cm in size who underwent a transperitoneal or retroperitoneal minimally invasive adrenalectomy by noon with no perioperative hemodynamic disturbances; these patients were discharged home the same day of surgery after a mean stay of just under 7 hours (4). Similarly, the following year, Edwin et al. published a cohort of 13 patients with Conn’s syndrome living in close proximity to the hospital who underwent laparoscopic adrenalectomy and were subsequently discharged within 3-6 hours (5). In the following 20 years, several additional studies on OMIA have been published that better define factors determining the feasibility of OMIA as described below.

Patient-related factors

OMIA has been shown to be feasible among patients with a range of sociodemographic and anthropometric characteristics. Age does not appear to be by itself a limitation to OMIA; most studies did not impose strict age inclusion criteria, with only two studies excluding patients older than 70 or 75 years [(4) and (30), respectively]. In two studies comparing patients undergoing inpatient versus outpatient adrenalectomies, age was not significantly different between the two groups (10,29); in the study by Shariq et al., inpatient and outpatient ages at the time of surgery were 52 and 50.5, respectively (P=0.25) (10) and in the study by Gartland et al., 56.5 and 56 (P=0.89) (29). Furthermore, no study has shown a difference in performance of adrenalectomy as an outpatient versus inpatient procedure based on patient gender.

In terms of patient physical status class, ASA of III or higher did not appear to be prohibitive to performing OMIA. In fact, the majority (63%) of patients included in a 2-center OMIA study were of ASA class III, and no statistically significant difference in ASA class was identified between patients undergoing an outpatient versus an inpatient procedure (ASA III: 63% vs. 72%, P=0.13) (29). Similarly, III was the mean ASA class among 15 patients undergoing robotic OA (31). Along the same lines, almost half (46%) of patients undergoing laparoscopic OA were of ASA class III in a study including data derived from the NSQIP dataset (10). The investigators, however, demonstrated that the outpatient group included a statistically significantly smaller portion of ASA class III patients (45.5% vs. 61%, P=0.003). Of note, this study preemptively excluded patients with ASA IV and V (10); similarly, another study excluded patients with ASA III, IV, and V (30).

Likewise, obesity was not a prohibitive patient-related factor, despite one of the studies excluding patients with BMI >40 kg/m2 (4). In Gartland et al.’s study of 99 OMIA patients at two centers, approximately half of the patients undergoing OMIA were obese with a median BMI of 31; this was not statistically different than the median BMI of 29 among patients admitted to the hospital (P=0.26) (29). In contrast, in the study by Shariq et al., although OMIA was shown to be safe among obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) patients, BMI was statistically significantly lower for the outpatient group (obese: 37% vs. 50%, P=0.04) (10).

Given that proximity of residence to hospital can theoretically influence the feasibility of performing adrenalectomy in an outpatient fashion, studies have used this factor either as an inclusion criterion, or have compared residence-to-hospital distance between the outpatient and inpatient groups. Indeed, both Edwin et al. in one of the earliest studies, and Skattum et al. in a study analyzing the feasibility of outpatient surgical procedures including adrenalectomy, excluded patients living >30 minutes away from the hospital (5,33). In the Gartland et al. study there was no statistically significant difference in terms of home-to-hospital distance between the outpatient and inpatient groups (median 48 vs. 51 miles, P=0.62), although the authors acknowledged that some patients undergoing OMIA may have stayed in a nearby hotel or with local contacts, data which were not captured in the study (29).

Tumor-related factors

Although most of the reviewed studies imposed strict exclusion criteria based on the underlying adrenal condition, OMIA has been shown to be feasible across multiple adrenal pathologies. These include adrenocortical adenoma (4,10,27-31), Cushing’s syndrome (29-31), primary hyperaldosteronism (4,5,10,28-31,33), myelolipoma (4,29), and metastatic lesions (27,29,30). No studies reported OMIA for patients with pre-operative surgical indication of adrenal cortical carcinoma. Two studies showed a higher frequency of primary hyperaldosteronism in those in the outpatient subgroup [14.8% vs. 6% (10); 27% vs. 14%, P=0.01 (29)]. The most frequently used pathologic exclusion criterion appeared to be the presence of pheochromocytoma, with multiple studies (4,5,10,30,33) preemptively excluding this condition. Despite this, studies that did include patients with pheochromocytoma showed that OMIA is safe among this patient subgroup. In one small single-surgeon robotic series of outpatient adrenalectomies, 2 of 15 (13%) patients had pheochromocytoma (31). In the largest OMIA series published to date (n=99), 14% underwent an operation for this disease (29); this percentage was statistically significantly smaller compared to the 28% of patients in the inpatient group who underwent a procedure for presumed pheochromocytoma (P=0.01).

Large lesion size was frequently cited as an exclusion criterion with different thresholds being used, such as 5 cm (4), 6 cm (30) or 10 cm (5). Gartland et al., who did not exclude patients on the basis of lesion size, found that patients discharged on the same day had statistically non-significantly smaller lesions (median size: outpatient 3.5 cm vs. inpatient 3.9 cm, P=0.07) (29). No study presented data specifically on bilateral lesions.

Operation-related factors

Same-day discharge appears to be safe following adrenalectomy performed using all standard minimally invasive approaches. These include laparoscopic transabdominal which was the most frequently described (4,5,28-30), robotic transabdominal (29,31) and posterior retroperitoneoscopic approach (4,27,29). Studies utilizing the NSQIP dataset do not include information on adrenalectomy approach given that NSQIP lacks this granularity (10,11). Outpatient adrenalectomy has also been shown to be feasible when performed as a single-port robotic procedure through a 2.5 cm incision; a single-surgeon prospective study of single-port robotic cases included 4 patients who underwent an adrenalectomy and were discharged the same day (26). The only study comparing operative approach between the outpatient and inpatient groups demonstrated a higher frequency of the robotic approach in the outpatient group (37% vs. 25%, P=0.13), however this association did not reach statistical significance and may be due to favorable patient factors (29).

Safety of OMIA

Within the limitations of patient selection and with the understanding that immediate postoperative complications requiring admission would de facto exclude patients from the outpatient subgroup, all studies describe OMIA as safe. No immediate postoperative complications after OMIA were reported in several studies (23,25,29). Gill et al. reported only one complication (abscess in the adrenal bed) among nine cases (4). In a published series using the NSQIP dataset, 30-day overall complication rate was 3.4% for the outpatient group and did not differ significantly from that of the inpatient group of 4.4% (P=0.99) (10). The same study reported 0% mortality and re-operation rate at 30 days. In another study, the 30-day complication rate of OMIA was statistically significantly lower compared to inpatient cases on analysis adjusted for surgical indication, tumor size, and patient factors including age, BMI and ASA class (4% vs. 15%, P=0.02) (29).

Several studies reported zero readmissions (5,23,29,30). Among 15 patients undergoing robotic-assisted OMIA, one patient was readmitted on postoperative day 15 with adrenal insufficiency (31). In the 2021 NSQIP study (10), there was an increased rate of 30-day unplanned readmissions for outpatient compared to inpatient procedures (5.7% vs. 2.9%, P=0.03), however, this association did not remain significant on multivariable analyses. In a multi-institutional study by Gartland et al., OMIA had a lower 30-day readmission rate on univariate analysis, but this was not statistically significant after adjusting for surgical indication, tumor size, and patient age, BMI, and ASA class (2% vs. 8%, P=0.09) (29).

Patient satisfaction and cost of OMIA

OMIA was found in one study (n=58) to be associated with similar “overall experience scores” compared to the inpatient group (9.12 vs. 8.93, P=0.367) using a phone survey based on the communication domain of the Outpatient and Ambulatory Surgery Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Survey (32). In another study using a 3-point satisfaction scale postoperatively, patient satisfaction was rated as “excellent” in 12 out of 13 patients (5). Skattum et al. used a 4-point scale to assess patient satisfaction post-operatively; satisfaction was “excellent/good” in 18 out of 20 patients (33). In several studies, OMIA has been associated with reduced healthcare costs, with the saved cost being directly attributable to the reduced number of hospitalization days (28,30,33). Specifically, Mohammad et al. estimated a cost saving of C$1,478 per case: C$326 saving on the day of surgery plus C$1116 for each day thereafter (30).

A summary of the available data on the feasibility, safety, patient satisfaction and cost of OMIA is shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| Feasibility |

| Patient-related factors |

| Age, gender: non-prohibitive |

| ASA class: non-prohibitive but lower ASA class has been associated with OMIA |

| Obesity non-prohibitive but OMIA has been associated with lower BMI |

| Tumor-related factors |

| Pathology: non-prohibitive, but (I) no data for ACC, (II) OMIA has been associated with higher frequency of primary hyperaldosteronism and lower frequency of pheochromocytoma |

| Tumor size: non-prohibitive |

| Operation-related factors |

| Minimally invasive approach/technique: non-prohibitive |

| Safety |

| Safe in terms of complication, readmission, re-operation and mortality rates when compared to inpatient minimally invasive adrenalectomy |

| Patient satisfaction |

| Good/Excellent |

| Cost |

| Decreased cost |

ACC, adrenal cortical carcinoma; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; OMIA, outpatient minimally invasive adrenalectomy.

Discussion

In this systematic literature review of available studies, OMIA is reported to be feasible across a wide spectrum of patients while exhibiting a favorable safety and cost profile. As shown in the results, minimally invasive adrenalectomy is performed in an outpatient fashion in adult patients of any age >18 years old, those who are obese, as well as those who are of ASA class III and above; it has also been described as feasible among patients harboring a variety of lesion/tumor types and undergoing adrenalectomy in any minimally-invasive fashion. Nevertheless, a limited number of patient, pathologic and perioperative characteristics have been found to be associated with a higher likelihood of discharging patients on the day of surgery, and this is likely largely secondary to pre-operative patient selection. These include lower ASA class, lower BMI and primary aldosteronism as the surgical indication.

While we and others report the safety of outpatient adrenalectomy in appropriate cases, we do not recommend performing adrenalectomy in outpatient-only surgical centers yet. Indeed, the decision to discharge a patient on the day of surgery could be influenced by several intra- and post-operative factors which cannot be determined pre-operatively, such as excessive blood loss, post-operative hemodynamic instability and laboratory abnormalities. Technical considerations may also influence the decision to discharge a patient on the same day; those include inadvertent injury or suspected injury to surrounding structures, large tumors requiring extension of port sites to extract the specimen, or tumor invasion of surrounding structures. Furthermore, any adrenalectomy patient may require resources not available in outpatient centers such as blood product availability and high-level anesthesia care. Fazendin et al. have described several factors that could potentially preclude OMIA; these are shown in Table 3 (21).

Table 3

| Clinical | Procedural | Social |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac or respiratory failure | Large tumor (>8 cm) | Excessive living distance from hospital |

| End-stage renal disease on dialysis | Intraoperative hemorrhage | No available caregiver |

| Anticoagulation | Perioperative hemodynamic instability | No available transportation |

| Severe deconditioning | Tumor invasion found intraoperatively | Communication barrier(s) |

| Uncontrolled blood glucose | Inadvertent injury to surrounding organ(s) | Patient preference |

This review reveals that the subject of OMIA has not been adequately investigated, as the relevant included studies have several limitations. Namely, we could identify only 13 studies that presented OMIA specific data, and of those, only two compared outpatient to inpatient procedures, albeit in a non-randomized fashion. Furthermore, the number of patients included in each study was small with some including as few as four subjects, while no study included more than 100 outpatient cases. The retrospective nature of the studies introduces bias. Indeed, no randomized trials were identified, precluding a direct comparison of outpatient to inpatient adrenalectomies. Instead, almost all studies were single-arm descriptive studies. Therefore, included patients were by definition those who did well enough to be able to be discharged on the same day; as such, even with matching, selection bias impacts any comparison of outcomes between inpatients and outpatients. Additionally, intent-to-treat analyses (intent to discharge on the same day) are lacking, thus the true success rate of intended OMIA has not been investigated.

Other limitations of the OMIA literature include the heterogeneity of study design (e.g., single- vs. multi-center vs. national database, single surgeon experience vs. institutional data), pathologies/surgical indications and surgical approach. They also include the lack of a standardized method to measure and report outcome metrics. Importantly, the existing literature also does not adequately incorporate several patient subgroups. The most notable example is the underrepresentation of patients with pheochromocytoma given that this indication for OMIA was excluded from at least 5 of the 13 studies. In some cases this exclusion appears to be based on disease physiology and how the use of long-acting alpha antagonists may impact perioperative stability (23); future studies may be more open to including patients with pheochromocytoma given that shorter-acting alpha antagonists like doxazosin are now commonly used pre-operatively, and given there are now several studies demonstrating the safety of discharging these patients on the day of their adrenalectomies.

The above appraisal of the existing literature does not aim to critique previous works, but rather identify potential areas of opportunity. Selection of appropriate patients, while an epidemiological limitation, is good patient care. In fact, the evolution from performing the first described minimally invasive adrenalectomy to discharging the patients only a few hours represents progress and improved patient satisfaction. Future work could benefit from larger and wider inclusion cohorts encompassing for instance all indications for surgical intervention, as well as from rigorous statistical analysis focusing on identifying candidates for same-day discharge. Accurately estimating cost savings and determining collateral benefits (e.g., minimizing in-hospital infection risk) will also be paramount. With more quality data on this subject, minimally invasive adrenalectomy may be more universally deemed as appropriate for the outpatient setting by insurers. The data presented herein could potentially facilitate a change in that regard.

In conclusion, based on the available literature to date, OMIA in appropriate candidates appears to be feasible, safe, cost-saving and associated with high patient satisfaction. While further larger studies should investigate the feasibility and benefits of OMIA in wider cohorts, recognition of minimally invasive adrenalectomy as an outpatient procedure by professional organizations and insurers is needed for wider adoption.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Robert Sutcliffe) for the series “Laparoscopic Adrenalectomy” published in Laparoscopic Surgery. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA-ScR reporting checklist. Available at https://ls.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ls-22-23/rc

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://ls.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/ls-22-23/coif). The series “Laparoscopic Adrenalectomy” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Morales-García D, Docobo-Durantez F, Capitán Vallvey JM, et al. Consensus of the ambulatory surgery commite section of the Spanish Association of Surgeons on the role of ambulatory surgery in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Cir Esp 2022;100:115-24. (Engl Ed).

- Specht M, Sobti N, Rosado N, et al. High-Efficiency Same-Day Approach to Breast Reconstruction During the COVID-19 Crisis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2020;182:679-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Comfort SM, Murata Y, Pierpoint LA, et al. Management of Outpatient Elective Surgery for Arthroplasty and Sports Medicine During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Orthop J Sports Med 2021;9:23259671211053335. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gill IS, Hobart MG, Schweizer D, et al. Outpatient adrenalectomy. J Urol 2000;163:717-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edwin B, Raeder I, Trondsen E, et al. Outpatient laparoscopic adrenalectomy in patients with Conn's syndrome. Surg Endosc 2001;15:589-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Assalia A, Gagner M. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Br J Surg 2004;91:1259-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rayan SS, Hodin RA. Short-stay laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Surg Endosc 2000;14:568-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Medical Association. Addendum E.-Final HCPCS Codes That Would Be Paid Only as Inpatient Procedures for CY 2021 2021 [Internet]. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/license/ama?file=/files/zip/2021-nfrm-opps-addenda.zip

- BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee. BlueAdvantage 2019 CMS Inpatient Only List 2019 [Internet]. Available online: https://www.bcbst.com/providers/2019-CMS-Inpatient-Only-List.pdf

- Shariq OA, Bews KA, McKenna NP, et al. Is same-day discharge associated with increased 30-day postoperative complications and readmissions in patients undergoing laparoscopic adrenalectomy? Surgery 2021;169:289-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sharma RK, Huang B, Lee JA, et al. SAT-156 Shorter Hospital Stays Are Not Associated with Increased Readmission or Complication Rates in Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Adrenalectomies. J Endocr Soc 2020;4:SAT-156. [Crossref]

- Beninato T, Laird AM, Graves CE, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the practice of endocrine surgery. Am J Surg 2022;223:670-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Plaza CP, Perales JL, Camero NM, et al. Outpatient laparoscopic adrenalectomy: a new step ahead. Surg Endosc 2011;25:2570-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wheeler MH, Harris DA. Diagnosis and management of primary aldosteronism. World J Surg 2003;27:627-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Turrentine FE, Stukenborg GJ, Hanks JB, et al. Elective laparoscopic adrenalectomy outcomes in 1099 ACS NSQIP patients: identifying candidates for early discharge. Am Surg 2015;81:507-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsuru N, Suzuki K. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy. J Minim Access Surg 2005;1:165-72. [PubMed]

- Dariane C, Goncalves J, Timsit MO, et al. An update on adult forms of hereditary pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Curr Opin Oncol 2021;33:23-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karanikola E, Tsigris C, Kontzoglou K, et al. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy: where do we stand now? Tohoku J Exp Med 2010;220:259-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chalkoo M, Awan N, Makhdoomi H, et al. Laparoscopic Adrenalectomy; A Short Summary with Review of Literature. Arch Surg Clin Res 2017;1:001-11.

- Fazendin JM, Gartland RM, Stephen A, et al. Outpatient Adrenalectomy: A Framework for Assessment and Institutional Protocol. Ann Surg 2022;275:e541-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Graves CE. Clinical Judgment and Experience Remain Critical Factors in the Safety of Minimally Invasive Adrenalectomy: Commentary on “Outpatient Adrenalectomy: A Framework for Assessment and Institutional Protocol.” Ann Surg 2022;275:e543. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stefanidis D, Goldfarb M, Kercher KW, et al. SAGES guidelines for minimally invasive treatment of adrenal pathology. Surg Endosc 2013;27:3960-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kraft K, Mariette C, Sauvanet A, et al. Indications for ambulatory gastrointestinal and endocrine surgery in adults. J Visc Surg 2011;148:69-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramonell KM, Fazendin J, Lindeman B. Review of Surgical Therapy of Adrenal Tumors in Guidelines From the German Association of Endocrine Surgeons. JAMA Surg 2021;156:1061-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abaza R, Murphy C, Bsatee A, et al. Single-port Robotic Surgery Allows Same-day Discharge in Majority of Cases. Urology 2021;148:159-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cabalag MS, Mann GB, Gorelik A, et al. Posterior retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy: outcomes and lessons learned from initial 50 cases. ANZ J Surg 2015;85:478-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gagné JP, Al-Obeed O, Tadros S, et al. Advanced laparoscopic surgery in a free-standing ambulatory setting: lessons from the first 50 cases. Surg Innov 2007;14:12-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gartland RM, Fuentes E, Fazendin J, et al. Safety of outpatient adrenalectomy across 3 minimally invasive approaches at 2 academic medical centers. Surgery 2021;169:145-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mohammad WM, Frost I, Moonje V. Outpatient laparoscopic adrenalectomy: a Canadian experience. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2009;19:336-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moughnyeh M, Lindeman B, Porterfield JR, et al. Outpatient robot-assisted adrenalectomy: Is it safe? Am J Surg 2020;220:296-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pigg RA, Fazendin JM, Porterfield JR, et al. Patient Satisfaction is Equivalent for Inpatient and Outpatient Minimally-Invasive Adrenalectomy. J Surg Res 2022;269:207-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skattum J, Edwin B, Trondsen E, et al. Outpatient laparoscopic surgery: feasibility and consequences for education and health care costs. Surg Endosc 2004;18:796-801. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Michelakos T, Altan D, Moore A, Lubitz CC, Hodin RA, Gartland RM. Feasibility and safety of outpatient minimally invasive adrenalectomy: a scoping review. Laparosc Surg 2022;6:25.